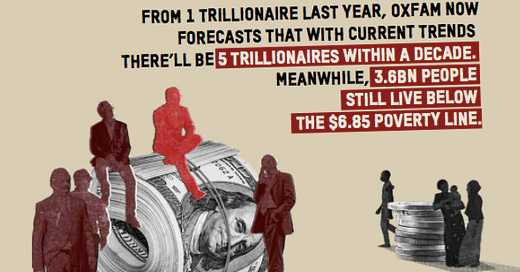

The race for five to become trillionaires in a decade. This is oligarchy in real time.

Op-ed by Meg Pirie, with insights from Oxfam

Image source: Oxfam ‘Takers not Makers’ report.

I am reminiscing back to a childhood game of Monopoly. The goal was always to get the most hotels on Park Lane and if you controlled transport too, you were always on to a sure thing. I remember the heated debates and joy of winning, yet lately the thought of the game itself stirs something else in me – a duplicity that I can’t put my finger on.

A small crow snaps me out of my train of thought. I am sitting in my favourite cafe and watch as it strategically takes a sachet of sugar out of a pot on an outside table and flies up to the glass roof above, opens the sugar, flicks it upwards and eats it in one. I wonder if it has a monopoly on sugar on this avenue. I think back to that word, monopoly and now understand the duplicity of the game – they were training us young to monopolise resources for the capitalist society in which we were to find ourselves, where only few at the top succeed. I reflect on the small crow with the probable sugar dependency – the way in which nature always adapts to its surroundings, but how we as people just seem to take, take, take.

As I write this, President Trump has been sworn back into Office in the United States, creating what seems like a hurricane of second-term measures including withdrawing from the Paris climate agreement; reneging on Biden’s diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) policies; proclaiming a national emergency against non-citizens; and signing an order for the highest North American peak, which was named Denali by indigenous Koyukon Athabascans, to revert back to its former name of Mount McKinley.

At his inauguration billionaires with a combined worth of $1.35 trillion attended – from the world’s richest person, Elon Musk; to Amazon founder Jeff Bezos; OpenAi’s CEO Sam Altman; as well as Meta’s Mark Zuckerberg. The fact that these billionaires are all men, is no coincidence. The fact that these billionaires are pivotal to the way our current society’s need for speed and tech operates, is also no coincidence. This is oligarchy in real time. The concept in which a small group hold all the power in a country. The fact that these corporations, infiltrate countries globally is significant.

I am telling you this, not to share my political views, but to show where we are now in 2025. A place in which a wealthy few have it in their power to support climate change measures; show empathy and kindness to people; and support Indigenous peoples and their knowledge, particularly in relation to land and climate issues. As it stands, this is not where we are currently.

Last month, Oxfam released their report ‘Takers not Makers’ which focuses on the unjust poverty and unearned wealth of colonialism. Despite the economy, climate and conflict crises globally, billionaire wealth surged three times faster in 2024, with five individuals now on track to be trillionaires within a decade. The report reminds us that we live in a deeply unequal world in which most billionaire wealth is taken and not earned, inciting colonial domination. This plays out via systemic exploitation where those in the marginalised groups bear the cost. Accordingly, this system extracts wealth from the Global South to the wealthiest 1% at the rate of $30 million an hour.

The report confirms that monopolisation of assets and wealth affects wellbeing in working class communities as well as those in the Global South. Alex Maitland, Oxfam’s International Inequality Policy Advisor said:

“In summary, a small number of ever-swelling corporations are wielding extraordinary influence over economies and governments, with largely unbridled power to price gouge consumers; suppress wages and abuse workers; limit access to critical goods and services; thwart innovation and entrepreneurship; and privatise public services and utilities for private profit.

“Monopolistic power begets more power, allowing monopolies to extract from firms and workers in their gravitational orbit, driving greater inequality and bodies like IMF agree this power is growing and contributing to inequality. It is driving an economy-wide transfer from labour to capital – redistributing ‘the disposable income of the many into capital gains, dividends and executive compensation of the few’. By creating scarcity to increase prices, therefore driving up profits, monopolies redistribute income and wealth regressively economy-wide: from workers and consumers, who are overcharged and overburdened by higher margins, to executives and owners, who are more likely to be rich and own stock.”

Around 18% of the world’s wealth comes from monopolising tactics and the UK is far from immune, with it cited as having the highest proportion among all G7 countries of billionaire wealth derived from monopolies. Alex confirms that this is due to the concentration of billionaire wealth in industries such as IT, telecoms and financial services, which are considered monopoly sectors. Alex said:

“We see especially high concentration of ownership in these sectors meaning individuals are likely to hold extensive equity – think tech companies that began as startups controlled by founders and hedge funds.”

Moving forward, Oxfam is calling on all governments, including the UK, to act urgently to reduce inequality and end extreme wealth through the following means:

Radically reducing inequality. Governments need to commit to ensuring that, both globally and at a national level, the incomes of the top 10 per cent are no higher than the bottom 40 per cent.

Taxing the richest to end extreme wealth. Global tax policy should fall under a new UN tax convention, ensuring the richest people and corporations pay their fair share. Tax havens must be abolished.

Ending the flow of wealth from South to North. Cancel debts and end the dominance of rich countries and corporations over financial markets and trade rules. Former colonial powers, including the UK, must also confront the lasting harm caused by their colonial rule, offer formal apologies, and provide reparations to affected communities.

Image source: Oxfam ‘Takers not Makers’ report.

Wellbeing as a central facet to a new economy

So, while the oligarchy plays out in real time, we need to focus our attention on what we can do and not on that which is out of our control. Last year, we at Fashion Roundtable brought out the ‘Creative Wellbeing Economy’ (CWE) framework, which looks at placing people and planet in an interwoven symbiotic relationship: revaluing locality, creativity, and enhancing accessibility to transformative tools and opportunities as links in a newly formed chain of opportunity.

While writing this, we understood that the current growth-at-all-costs model, without sustainability and social justice as core drivers, was crashing and burning, not only our economy but also our climate, whereby very few with short-term goals were gaining at the expense of the rest.

With this in mind, the Creative Wellbeing Economy focused on placing wellbeing and the creative industries at the heart of its plans for economic growth. This centred on hyper-locality which looks specifically at the cultural needs of a particular place with community wellbeing at its core, requiring long-term vision and national renewal and not short-termist policy decisions.

Professor Tim Jackson’s argument that dismantling the current system requires offering people, “viable alternatives” is pivotal here. This requires keener policy attention on how communities, social participation and wellbeing can be allowed to flourish. Policy must therefore have at its heart a meaningful and lasting prosperity, building on how people and communities can thrive outside of the current system. Under the CWE framework, this prosperity comes from supporting social mobility; nurturing future, resilient leaders through a STEAM education; a revaluing of skills and community; cultural and heritage preservation; placemaking with hyper-locality in mind; as well as food and fibre sovereignty.

So, as the US, along with big tech roll back on DEI measures, we need to bulldoze forward with firmer and more just and equitable measures.

As minority groups are marginalised further, we need to hold space for them to speak out.

Instead of taking back from those within indigenous communities, our focus should be on giving more. As the climate emergency becomes more and more profound, they have the answers and are best placed to regenerate ancient lands.

To do this we must look towards wellbeing, a new direction in which the game of monopoly stays where it belongs, in the box.

For more on the CWE framework, click here.

For more on Oxfam’s ‘Takers not Makers’ report, click here.

“I am telling you this, not to share my political views, but to show where we are now in 2025. A place in which a wealthy few have it in their power to support climate change measures; show empathy and kindness to people; and support Indigenous peoples and their knowledge, particularly in relation to land and climate issues. As it stands, this is not where we are currently.” Meg Pirie – Fashion Roundtable’s Head of Sustainability and Regeneration Policy

It is really hard to take a think piece seriously when oligarchy is misspelled in the title and in the piece. Writers absolutely must do better.

Oh dear. This sort of semi-informed left wing rant gives a bad name to the occasional valid point and good social behaviour.

ps fact check: I think it is Park Lane in monopoly, not Avenue; also, rarely a winning strategy to focus on those two properties